The COVID-19 pandemic and the research lab

With self-isolation and quarantine procedures being in effect in almost every country across the globe, researchers have found themselves having to adapt to a life of working from home – with all the included perks and challenges.

Since COVID-19 closed my office on 12 March, I’ve tried to keep working with a mindset of business as usual. But as an academic with data readily available for analysis, and a person with no children, I felt quite lucky, relatively speaking. Subsequently, my intrigue was captured by how other researchers might be affected by this pandemic, specifically those with less fortunate home-working circumstances as myself.

With this in mind, I asked ‘#AcademicTwitter’ how the pandemic is affecting their scientific lab work and working lives. Here are some of the most popular themes I came across:

Become a member of Neuro Central to receive regular updates

Home office challenges:

Many individuals reported experiencing difficulty in seperating their home environment from a working one. Here, one of the most common issues was that they had ‘little space’ and ‘no home-office desk’. People also stated that it was mentally difficult to ‘switch’ to home-office without this privilege of more space or an entirely separate room to work in.

There’s also the matter of lack of office supplies such as printers, scanners, notepads, etc, which has made administrative tasks really difficult to carry out. Others working with large data have struggled to do so at home due to lack of computer processing power and storage availability. With no home-office or desk, I have found myself working mostly on the sofa. I don’t have a spare room or the space to set up an entire desk in the apartment so if the sofa gets uncomfortable I resort to the dining table. Others I know have invested in office supplies, a new desk, or a more back-friendly chair, things that improve morale almost as much as the home office set up.

Teaching issues:

With universities and schools being closed, many teachers and lecturers have had to adapt to virtual teaching. Senior professors have found themselves in a ceasefire with their worst enemy; technology, as their options were reduced to adapt or perish. Joking aside, a little closer look under the hood reveals that teaching online has also been challenging, with some students not even being able to attend classes due to lack of internet access. With no short-term solution, these students have simply had to not get their education while others do, a problem that reflects the wider disproportionate impact the pandemic has on those in less privileged circumstances. Some of those that do have the access have found that it is harder to concentrate on the content, reporting a higher compulsion to check their phones or let their mind wander during online talks. It seems concentration and engagement is a challenge even with virtual alternatives.

Halted experiments:

The degree to which experiments have been affected has varied between persons and research groups, with much of it depending on the type of data collection people rely on. Experiments that are reliant on an individual being present in a lab have been completely shut down. A lot of people simply cannot do the work they need to do from home. Where data collection has not been completely cancelled it has been delayed, a disruption felt by the subsequent parts of the research process, all of which push back project deadlines while many employees watch their contracts run down.

Alberto Bardelli, a molecular geneticist at the University of Turin (Italy), describes the incredible effort to close his wet-lab in 48 hours: “With no time to dither, we made a list of priorities. The most important thing was to freeze organoids grown from the cells of specific patients, which we use to assess how different therapies would work – these are unstable, fragile and, most importantly, unique, just like the tumors from which they originated. Will they grow again? We hope so, but can’t be sure. Next, we made sure that animal experiments would be completed properly and, whenever possible, rushed to complete ongoing cell-based drug screens and biochemical studies. The response was remarkable: everyone in the lab worked non-stop, helping out until late. The 48 hours went by very fast. Once the lab was empty, it was with a heavy heart that I walked down the corridors for a last look at the tissue-culture hoods” [1].

Students:

Some students have been pressured to return to their labs to continue data collection and lab work, despite the risk it poses on them. The risk of getting a bad grade or not satisfying their PI’s demands feels higher than COVID-19 infection risk. Other students noted feeling worry about graduation dates, extensions to deadlines, funding insecurity and general uncertainty about the future. Additionally, there remains the worry about not having enough time to collect the data needed for their theses. International students have the added worry of expiring visas and having to go back home without the degrees they’re paying for. A big concern most noted by PhD candidates in the last months of their contracts was the uncertainty of the job market and whether or not their funding and/or contracts will be extended. If the whole world has been set on pause, why shouldn’t their contracts also be?

Others have had better experiences, with deadlines being pushed back and a lot of support coming from their institutions. My own institution, the University of Oslo (Norway), have ensured PhD candidates understand their right to an extension should their “research progression be effectively prevented as a result of the corona situation.”

Productivity and psychological impact:

Ruminating on current events has had an impact on productivity too. Many are struggling to concentrate due to worry about their family members and friends. Additionally, self-isolation has been difficult. Those that describe themselves as extroverts feel they miss social events more than others that might not prescribe to an extroverted personality, and describe themselves as being stuck inside.

While many have noted Zoom and other social media platforms have helped with the loneliness and isolation, others feel the novelty of such platforms has passed and it now feels more like a chore. Moreover, the lack of personal interaction makes it difficult to recharge batteries for when people do need to work.

People also explicitly reached out to inform of having a mental illness but no psychologist to talk to, or feeling much more lonelier and sadder as of late compared to their usual mental state. A slow deterioration in mental wellbeing or general optimism about life was common and this seemed to mirror the work productivity efforts.

For academics, productivity and psychological impact rarely exist exclusively to one another. The feeling of uselessness is an almost inevitable aftermath of not being productive, even though the lack of productivity we are seeing is a natural consequence of the circumstances we’re in. We seem almost hardwired to agonize ourselves with the same level of guilt and disappointment in ourselves despite the changing circumstances. This is not viable during a pandemic where there are enough mental stressors plaguing us.

Personally, I feel like my academic productivity pulls hardest on the strings of my mental wellbeing. Whether it be joy, how accomplished I feel, or even right down to my self-worth; I’m a puppet to my academic achievements. But for the time being, I’m halting this unfortunate reality. One day maybe I’ll manage to cut the strings off altogether.

Silver linings:

While a lot of researchers have struggled, some have thrived and managed to concentrate on reading literature and writing grants without the disturbance of upcoming experiments. Those with data collected earlier on in their projects have had little work-related disturbance aside from the change in work environment. Others have stated that they don’t feel the external pressure to work at certain times, and so can utilize their energy when it’s at its peak rather than forcing several coffees down early in the morning after a long commute. For those that usually get easily distracted, the pandemic has emphasized how large task-switching costs are when they are in the office, and how much energy is spent trying to cope with background noise and office distractions.

Parents in academia:

Children are particularly biting a big portion of the time-pie of academic parents, with babies needing plenty of care and attention and children needing homeschooling. Many parents exhaustingly report just trying to work when they find the time around the playtime/sleeping schedule of their young, and doing so with whatever energy the gods help them muster.

Guilt was not a stranger to academic parents, with some parents feeling guilty for avoiding work to take care of their child, and others feeling guilty for avoiding their child to take care of their work.

Women in academia:

The most staggering discovery relates to that of unbalanced productivity between men and women. In a recent Nature article titled, ‘The pandemic and the female academic’ [2], Alessandra Minello (University of Florence, Italy) highlights how the changes in productivity, which disproprotionately impacts women, will go on to affect careers in the long run. With care work being unbalanced, Minello expects data on publication records over the next couple of years to show parents and women in academia as disadvantaged relative to non-parents and men in 2020.

This is a something editors of journals have also picked up on in the last month, with early signs that the data supports exacerbated gender inequality:

Conclusion:

Among the themes, the most common issue people wanted to discuss was their lack of productivity. Generally speaking, the biggest descrepancies existed between those: with children and those without, larger versus smaller living spaces and the availability of a home office or not. Of course there are a whole host of individual differences at play, and even more variation in the factors that influence how we are affected. But for now Id like to focus on that which binds us.

No matter the differences in our circumstances or the country we’re in, we are all academics experiencing this pandemic together. My advice, as hackeneyed and unsophisticated as it may be, is to be kind to yourself during these unprecedented times. Staying connected is also important, so don’t underestimate the value of virtual meetings and hang-outs. If you can carve out a designated working space at home, do so, as this does help. If you have children, may the odds be ever in your favor, and try not to feel guilty for endulging in their company instead of working. Be understanding and empathetic with your colleagues, whether they’re students or professors. Rememeber, you’re not stuck inside, you’re safe inside. And last but not least, prioritize your mental health.

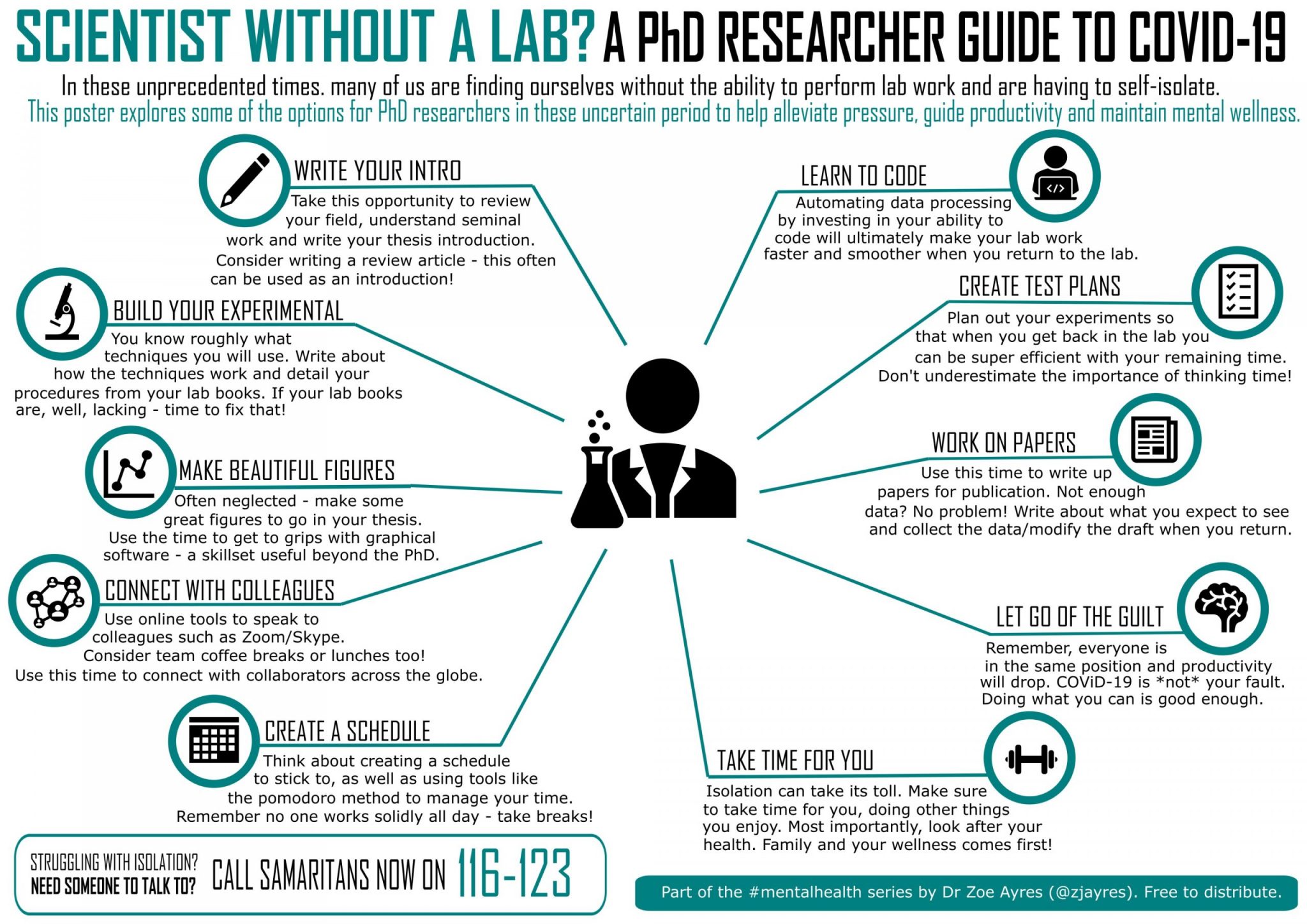

If you’re looking for more ideas for how you can spend your time, an infographic by Dr Zoë Ayres provides a helpful guide for us:

[1] Coronavirus lockdown: what I learnt when I shut down my cancer lab in 48 hours.

www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00826-7

[Accessed 26 April 2020]

[2] The pandemic and the female academic.

www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01135-9

[Accessed 22 April 2020]

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Neuro Central or Future Science Group.

You might also like:

For further updates regarding the coronavirus pandemic, visit our dedicated COVID-19 Hub here.