Ask the Experts: refractory epilepsy

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders in the world. It is characterized by seizures, caused by excessive electrical activity within networks of neurons in the brain. Although there are treatments available, not all people with epilepsy respond to them – this is called refractory epilepsy.

In this ‘Ask the Experts’ feature, Mark Richardson (King’s College London; UK), Andrea Ryan (Shape Network; London, UK), Caoimhe Twohig-Bennett (Epilepsy Research UK; London, UK) and Agnese Cattaneo (Angelini Pharma; Rome, Italy) discuss their perspectives on refractory epilepsy, including unmet needs and a new data-driven research project and the implications it could have on the epilepsy community.

What is refractory epilepsy?

Mark: Broadly, refractory epilepsy is epilepsy that fails to respond to available treatments. There is a strict operational definition from the International League Against Epilepsy that says that it’s the failure of two successive single drugs used at an adequate dosage for an adequate period of time. Essentially, it’s epilepsy that doesn’t respond well to current treatments.

What impact does refractory epilepsy have on the lives of those affected by it?

Andrea: My son was diagnosed with epilepsy just before his 12th birthday. He went through five medications, and his seizures just continued to worsen. It impacted everything. He was at the age where, as a parent, you start loosening the reins and let them experience things on their own and become more independent – he had just started secondary school so was getting public transport to school by himself. It meant we had to rein it all back in. We were told by his neurologists that he couldn’t go skiing, he couldn’t skateboard – all the things he loved doing, it just wasn’t safe for him to do them anymore. It had a real impact on his self-esteem, friendships, education, social life, day-to-day activities, and impacted the wider family life as well. Everything would change in a moment with a seizure – plans we had that day wouldn’t happen, or they would turn into a trip to A&E. He would often start his day in the school medical room from the side effects of the medication and miss the first couple of lessons whilst he slept them off – the doses were so high that a lot of the time the side effects of the medications were worse than the seizures themselves.

I recently looked at the seizure log we kept, which I haven’t looked at for a long time, and it reminded me just how life impacting it was for him. He dealt with it incredibly well. I think if there are any positives that have come out of it, it’s that he has become a very resilient 19-year-old.

What are the unmet needs of people with refractory epilepsy?

Andrea: Just the ability to get control. As a parent, you see pediatricians and neurologists, and they tell you to try medications, and when they don’t work, they tell you to try something else. You learn along the way that the more medications they try, the less likely it is that anything is going to work. My son was put on the surgical pathway at Great Ormond Street Hospital (London, UK) and had a couple of procedures, so we were quite lucky. You get used to that way of life and things changing at the drop of a hat. He would pick himself up and brush himself down and get back on with things. But it was hard, and it had a big impact on his mental health and behavior.

Why do you think there is a gap in research in refractory epilepsy?

Caoimhe: Despite epilepsy being one of the most prevalent, serious neurological conditions, it is subject to stark research funding inequalities. We know that, from data in recent years, just 0.3% of the total £4.8 billion that is spent on health-related research in the UK is invested in research into epilepsy. This is significantly disproportionate considering there are over 600,000 people in the UK with a known diagnosis of epilepsy and that epilepsy costs the NHS around £2 billion each year.

We have compared epilepsy research funding to funding for other neurological conditions such as dementia and Parkinson’s disease. In terms of health-related research investment, for dementia, the UK government invests around £100 per person living with dementia and for Parkinson’s disease, around £234 is invested per person living with the disease. For epilepsy, just £21 is invested for each of the 600,000+ people living with the condition.

This research funding inequality means that progress in finding new treatments has been slow, and this undoubtably has an impact for people with refractory epilepsy. Of the 600,000 people living with epilepsy, one-third have epilepsy that does not respond to medication or treatment. So, there’s a huge proportion of people with epilepsy that are being affected by chronic underfunding of research.

Can you give us an overview of the new data-driven research project for uncontrolled epilepsy?

Mark: The project essentially seeks to unpack the enormous amount of information that’s in electronic hospital medical records and create insights from that information.

A large amount of what we know about epilepsy is from research trials. In a typical research trial, a group of people with epilepsy is recruited, and those people are intentionally rather similar. The results from the trial tell us how a certain intervention works on average for that similar group of people. That’s critical information, as it may tell us whether a new drug works or not; however, it doesn’t tell us if that drug will work for a particular individual sitting in front of me in a consulting room. Trials throw away the immense variability between people with epilepsy, so that I don’t know whether a treatment will work for an individual or not, and the more different they are from people typically recruited in trials, the less confident I am.

The other side of the coin is that medical records are no longer kept on paper, they are in electronic databases in hospitals. Often individual hospitals will have health information from perhaps 1 million people. That’s an extraordinary resource.

The way I see this is that each person is, in a sense, their own individual clinical trial. They have tried different investigations to determine their diagnosis and different treatments to try to reach a response to their seizures or cure. But all that information is locked away in health records, and there are multiple challenges using it. One challenge is that data are, quite rightly, securely held for data privacy and protection reasons. Secondly, information is often in proprietary databases – databases that are specific to the particular test or the particular hospital – and getting the data out is hard. Thirdly, there is an enormous amount of that data – there may be a billion different documents in medical records in an individual hospital. Lastly, and crucially, although much of the data are structured and in a tabulated database – e.g. numerical results from blood tests – a lot of the important rich data is written in text. It’s written in real time by busy clinicians seeing patients in the hospital, and it’s written in whatever form of words they chose to use that day. It’s full of abbreviations, acronyms and misspellings, and sometimes inconsistent use of terminology. So, extracting the information and meaning is incredibly difficult.

This project has three aims. First, it is to extract, harmonize and make available all the electronic health records from the multiple different systems in the hospital. Then, secondly, to apply something that’s called natural language processing, which is a subset of artificial intelligence that has become highly developed over the last few years. Natural language processing can identify the meaning of particular terms in text, it can relate terms to one another, and it can annotate free text in detail and extract meaning and structure from it. Using this, we can create a trajectory for each individual from their medical records: How did their epilepsy start? What are their background, medical and personal features? What investigations did they have? What treatments and in what order? What was the response? We can put all that information together into one place.

The third aim is to use other kinds of artificial intelligence to try to extract things from that information that predict outcome. Understanding more about features of an individual’s experience with epilepsy might help determine which drug or drug combination to use or which drug not to use.

We want to collect and harmonize health information and make it usable, extract the meaning using natural language processing, and then create models where we can predict the features that associate with a response to medication.

How do you hope to use the conclusions from this project?

Mark: What I anticipate is based on what we have already seen with this kind of system. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a model using essentially the same components was deployed very quickly. They used medical records to identify risk factors for those admitted to hospital with COVID-19. They could determine those who might do better, and quickly flag people at high risk of deterioration and step up their care. This helped accelerate high-risk people to intensive care units, focus specific treatments and reach better outcomes. So, we have already seen that this kind of tool works in identifying people who will respond to particular treatments and accelerate better outcomes for them and across the board.

From this project, I expect we will develop some predictive models that we could implement in electronic health records in hospitals in real time and say, “Okay, for this person who’s this age, this gender, has these clinical features, has tried these other medications before, perhaps has these other health conditions as well, this is the most likely pathway to get that person seizure free.” Then, there would be an interesting question – does that work? That would potentially be another trial.

There is a gap in research around refractory epilepsy, which partly stems from the reality that epilepsy is multiple different conditions with multiple different causes, making research studies difficult. One of the advantages of using information from everybody with epilepsy is that it addresses that trial gap. So, if a trial has been conducted in a specific group of people with epilepsy and an outcome is relevant to that group, but maybe not everybody else, how do we start to assemble information that’s relevant to every individual? This system of accessing medical records at enormous scale starts to cast some light on that gap and may allow us to create predictive tools that are relevant to people who are not typically included in trials.

What could this research mean for people living with refractory epilepsy?

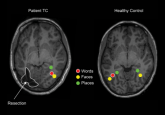

Andrea: I think it could be groundbreaking. There is so much data out there, but it’s difficult for clinicians to make sense of it. I hope that it will enable trends to be identified and patterns to be spotted. I believe a lot of refractory epilepsy, not only is it refractory, but we don’t know why it’s there, which is the case with my son. They are pretty sure he has a structural abnormality within his brain, but it’s so small that two invasive EEGs have not been able to identify it. It could make a huge difference just by piecing this together.

I think it gives hope to people affected by epilepsy, because as Caoimhe mentioned, there is a lack of research. It’s one small step but having these types of projects and collaborations could mean a huge change. It could mean that more people find control sooner and minimize the impacts on their lives. They can carry on living as they should, without interruption and constant fear.

What are the implications of this work on the wider epilepsy field?

Agnese: I think there are several implications. The digitalization of research will ultimately bring a more sustainable research approach, helping fill the gaps in a field where resources are often limited and minimizing further impacts on patients’ lives. This research is also taking the patient’s unique challenges and needs into account, as well as seeking their involvement and endorsement in the decision-making process. I think that this is a great example to continue paving the way in this sense of patient centricity.

Finally, this is a great example of how we in industry can work together with patient organizations and research institutions with integrity – in a way that is the most fruitful for patients. These kinds of partnerships are not unprecedented, but could be broader. For refractory epilepsy, our goal is creating a tool that can predict and help manage the condition as soon as possible, with the ultimate goal of making life better for patients.

Could this AI tool be used to investigate risk factors other than brain health conditions?

Mark: Yes, tools like this are broadly applicable across healthcare, particularly for common conditions where there is lots of data and variability within that condition.

What do Angelini Pharma and Epilepsy Research hope to achieve for people with epilepsy in supporting projects such as this?

Agnese: There is still a lot of work to be done in the epilepsy field, not just in research but also around awareness and stigma. Angelini Pharma is supporting various other projects, including projects relating to women and epilepsy and epilepsy in emerging countries. We’re also working on a project called Headway with The European House – Ambrosetti, which brings several stakeholders together to discuss what can be done for people with epilepsy from a multi-stakeholder and governmental perspective.

Caoimhe: From Epilepsy Research UK’s perspective, we know that the epilepsy research community is small and has limited funding resources for research. But as a community, we are so much stronger together and collaborations with ourselves and industry are important for driving innovations in research that will translate through to people living with and affected by the condition. Epilepsy Research UK was proud to set up The Shape Epilepsy Research Network, which is over 300 people affected by epilepsy who are interested in research, people such as Andrea. Working in this collaborative way helps ensure that the priorities of people affected by the condition are central to research into epilepsy. I think this project is a great example of industry and charities working together with academia to try and drive patient-focused solutions. It’s great to be aligned in a common purpose of trying to improve the lives of those affected by epilepsy.

Meet the experts

Mark Richardson | Paul Getty III Professor of Epilepsy, Kings College London (UK)

Mark Richardson is the Paul Getty III Professor of Epilepsy and Head of the School of Neuroscience at Kings College London. His primary research focus is the neurobiology of epilepsy and seizures. In collaboration with mathematicians and engineers, his research lab constructs models of the human brain using a range of imaging and neurophysiological techniques to understand the underlying mechanisms of seizures and related phenomena.

Agnese Cattaneo | Chief Medical Officer, Angelini Pharma (Rome, Italy)

Agnese Cattaneo | Chief Medical Officer, Angelini Pharma (Rome, Italy)

Agnese Cattaneo has been Chief Medical Officer of Angelini Pharma for nearly 6 years, overseeing a variety of initiatives for engaging with the clinical community and wider healthcare ecosystem across numerous disease areas. Subsequent to medical and doctoral training, including the publication of peer-reviewed research in pioneering journals such as the European Journal of Endocrinology and Clinical Endocrinology, Agnese held senior medical affairs positions at a number of companies, including Novartis (MA, USA) and AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK).

Andrea Ryan | Shape Network, Epilepsy Research UK (London, UK)

Andrea Ryan has been working in Financial Services for over 20 years. Andrea’s 19-year-old son Archie has epilepsy and has been seizure free for over 2 years following a thermocoagulation procedure at Great Ormond Street Hospital (London, UK). Before this, Archie had uncontrolled epilepsy that would not respond to treatment. Andrea is now a trustee at Hope for Paediatric Epilepsy London (HOPE), a London-based charity that supports families caring for children and young people with epilepsy and donates anti-suffocation pillows to children and young people with nocturnal convulsive seizures.

Caoimhe Twohig-Bennett | Director of Research Partnerships, Epilepsy Research UK (UK)

Caoimhe Twohig-Bennett | Director of Research Partnerships, Epilepsy Research UK (UK)

Caoimhe Twohig-Bennett is Director of Research Partnerships at Epilepsy Research UK, the only UK charity exclusively dedicated to driving and enabling research into epilepsy. Epilepsy Research UK drives and funds strategic, collaborative programmes to capacity-build epilepsy research, and recently funded and led the UK Epilepsy Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) to gather the evidence required to enable strategic investment in research. In 2022, Epilepsy Research UK launched #Every1EndingEpilepsy – a national research collaborative to deliver on the research recommendations published in the WHO IGAP, NICE Guidelines and PSP.